Personalized product ranking: a pillar of e-merchandising for better conversion and loyalty

Product ranking is a key component of any e-merchandising strategy. Behind this somewhat technical term lies a well-known business principle: ordering products in a way that maximises their visibility and sales potential. This logic is not new to the digital world; it has always existed in physical retail. Products placed at eye level attract attention and sell well. This is true on the shelf and even more so online.

On a web page, this 'eye level' is known as the 'fold'. It is what the user sees before scrolling. It is an extremely valuable space that is both limited and decisive. This is because 75% of activity is concentrated on the first page and almost half of this is on the first set of results that are visible without any effort [1]. This means that browsing is becoming an important e-merchandising tool for increasing sales.

This is all the more important since it is expressed through the two main entry points to product data sheets: listing pages and search results. These are the first interfaces that web users explore. What they see — or don't see — directly impacts their buying behavior.

Browsing guides the eye, influences decisions, and steers the purchasing path. This is why it is often confused with e-merchandising, as both focus on displaying the right products in the right place to maximize visibility and performance.

So what is a good ranking?

It's a subtle balancing act between three complementary logics:

First are the fundamentals of commerce. This includes displaying what people like, what they buy, and what's available. It shows the products that perform well and the bestsellers. This is nothing new. I remember visiting an Amazon store in Seattle where the shelves were organized just like on their website, with "Best Sellers of the Week" shelves. That's how it works. You have to show what sells.

However, it must still be available. In the digital sector, it's impossible to keep a product on the shelf if it's out of stock. The same goes for variations. If only quadruple XS or quadruple XL sizes are left, it has to come down, no matter how good it is. You can't sell what you can't deliver.

The second logic is commercial interest. We often talk about sales figures, but what really counts is the margin. Some products generate more than others, so it's in your interest to highlight them. The same goes for stock levels. The longer an item is out of stock, the higher the cost. With the rise of retail media, a new variable has entered the equation. Certain locations can now earn money directly via sponsored campaigns "on behalf of" other companies. This is a game-changer, but what is promoted by retail media does not always correspond to what performs well or generates the highest margin...

Then there's a third element that is often underestimated: customer interest. What do they really want to see? Their tastes, preferences, and context. This is undoubtedly the most difficult aspect to capture, but also the most valuable. After all, a good browsing is one that recognizes the individual behind each click.

In short, a good browsing reconciles three factors: sales, company goals, and user preferences. This is a key balance in any effective e-merchandising strategy.

Don't miss our expert advice: An introductory guide to e-merchandising

From static to dynamic ranking: a new era for e-merchandising

When I first started working in this field, I was told that we simply had to recreate the in-store experience online. We were told that we had to "express the range" from the lowest price to the highest, as if we were lining up products on a shelf. Some people might smile at that today and rightly so. We now know that static e-merchandising no longer meets today's challenges. Today's visitors expect a dynamic, personalized experience.

1) Manual

In the early days, browsing was 100% manual. Sometimes it was even referred to as visual merchandising. There were two approaches: those who wanted it to look pretty and those who wanted it to sell. The process was static. A product that was out of stock remained at the top of the list, no matter what. Above all, the browsing was the same for everyone - one size fits all.

This was in the early 2000s. And at the time, it was already a real step forward: we had understood that the order of display had an impact. No more random page sorting. The pioneers? Those who were used to distance selling. Les Trois Suisses, La Redoute... the precursors, well before e-commerce as we know it today.

2) Dynamic

Then we entered another era, around 2007-2008: that of dynamic browsing. Gone was the 100% manual approach. Rules, in-house algorithms and more or less clever cocktails were used to sort products according to specific criteria. It was still one size fits all, but at least it was dynamic.

The browsings were somewhat adapted to the current reality as the catalog was updated. For example, a product that was out of stock would drop down, while a bestseller would rise. We used basic business data such as availability, sales, and sell-through rates. However, web sales were still marginal at the time. Therefore, to build a good browsing, you often had to gather information from the physical store. Without that information, the sort would be irrelevant and even counterproductive.

3) Manual/dynamic mix

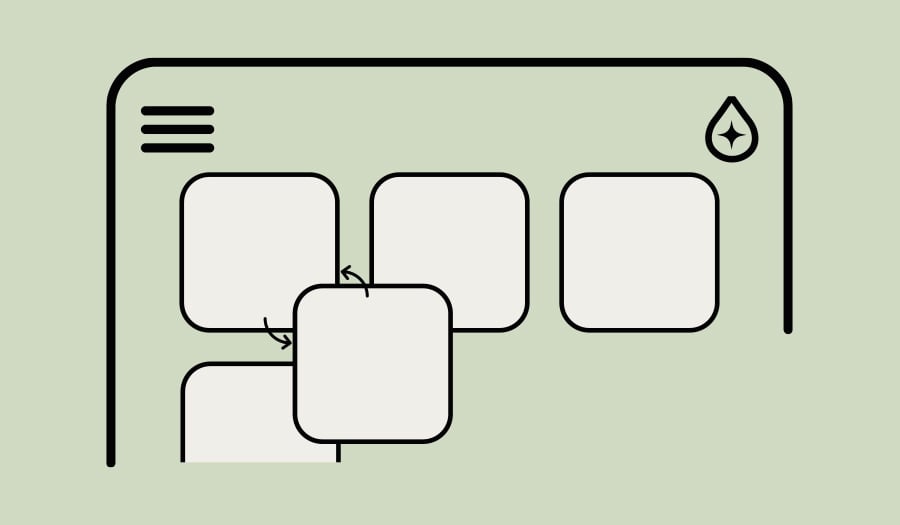

Then came more advanced solutions that combined the best of both worlds. They were a mix of manual and dynamic logic. It's still invaluable to be able to intervene manually and say, "I want this product to be in the first position." This could be for a retail media campaign, to sell 54 containers, or simply because a high-margin item deserves to be highlighted. This manual control and ability to "disengage" remains essential. Once again, all customers have the same browsing.

4) Segmentation

Then, we took it a step further with segmentation. Instead of offering a single browsing, we adapted it to a number of major customer profiles. There were three or four basic segments, each with its own browsing that was usually recalculated at night. This meant that, initially, users might see a browsing that didn't correspond to them. However, as their behavior progressed, the system refined their positioning: "Ah, maybe they're in that segment." It's an interesting logic — the buying journey has always existed — but it remained fairly static, with a few standard browsings applied to groups of customers.

5) Today, we can go much further

We now combine the best of both worlds: manual and automatic, dynamic and real-time. We define rules and make human decisions, but we also rely on self-learning, predictive, and truly individualized systems. That's exactly what next-generation e-merchandising is all about, and that's exactly what Sensefuel does. Find out how here.

What does this mean in practice? Each individual's browsing is unique. It is predictive and based on similar behaviors to anticipate what will work. It is self-learning and integrates more than a hundred signals linked to the fundamentals of commerce in real time. Above all, it's real-time, so there's no need to wait for a new visit. Every click counts, and every session is an opportunity to adapt the browsing. This level of finesse is only possible thanks to this technology. This technology brings real value to e-merchandisers.

You see a clear visual representation of the ranking. Two users are searching for trainers: one for himself and the other for his daughter. The engine understands each user's intention and displays the most relevant products at eye level. Although the range remains the same — 1,795 products — the browsing is completely different.

You see a clear visual representation of the ranking. Two users are searching for trainers: one for himself and the other for his daughter. The engine understands each user's intention and displays the most relevant products at eye level. Although the range remains the same — 1,795 products — the browsing is completely different.

That's one to one. That's real time. And that's exactly what individualized e-merchandising can offer.

[1] source: Sylvain Duthilleul, e-merchandising.net.